Molecular Diagnostics in Lung Cancer – Considerations and Relevance for Treatment Selection

The third session of the Roundtable Meeting was co-chaired by Matti Aapro, President of the European Cancer Organisation, and Geoff Oxnard, Vice President, Global Medical Lead, Liquid Franchise at Foundation Medicine.

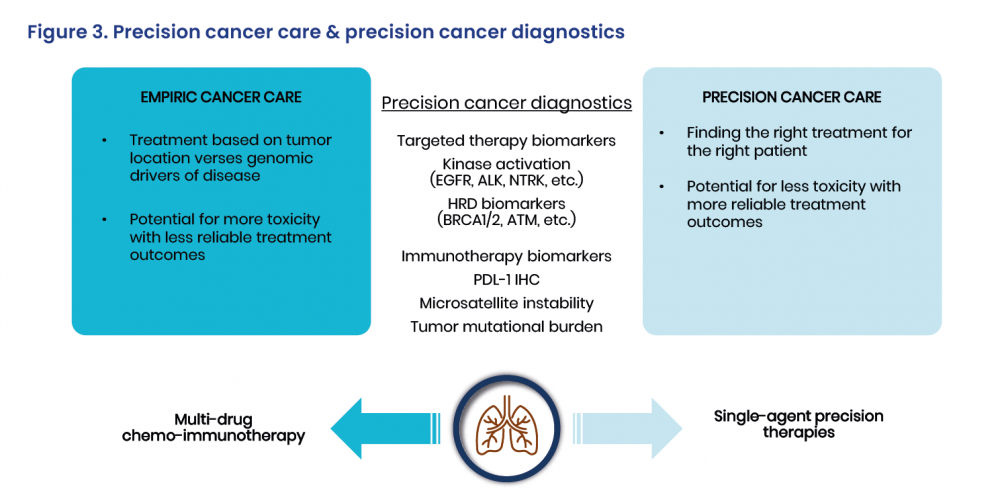

Oxnard opened by underlining the need to transition patients away from empiric cancer care, in which treatment is guided by tumour location rather than the genomic drivers of disease, and towards precision cancer care, which involves finding the right treatment for the right patient.

Lung cancer is the ideal candidate for this kind of shift as, without precision diagnostic testing, patients end up receiving multiple therapies with the potential for greater toxicity and less reliable treatment outcomes, all at a greater overall cost than if they were given single-agent therapy with greater benefits and less toxicity. The question is, however, how to implement that shift.

A Revolution in Understanding

Matthew Krebs, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Experimental Cancer Medicine, University of Manchester and Consultant in Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK, explained that, traditionally, lung cancer was considered and classified in terms of its histology, divided into non-small cell and small cell lung cancer with further histological subtypes for non-small cell lung cancer, besides being characterized for the use of immunological approaches.

There is now a greater understanding of the disease, and with the revolution in genomic profiling the number of sub-classifications has risen from just three in non-small cell lung cancer in 2004 to more than 25 today. These advanced diagnostics have led to the identification of numerous actionable genetic alterations via genomic profiling, such as in the EGFR, ALK, ROS1, RET and TRK genes, thus allowing precision treatment to be chosen. For patients, this has meant a dramatic revolution in the care of lung cancer and other disease types, with novel oral medications achieving fantastic responses and improved survival.

Several genetic alterations are therefore recommended for testing, as well as many more that should be assessed depending on the availability of next-generation sequencing, as discussed by organisations such as the European Society for Medical Oncology.[12] Few of those tests are actually performed in routine clinical practice, however.[13] Moreover, Krebs said that the availability of testing is likely to be highly variable across different centres.

Even when genomic testing is performed, centres typically use older technologies. While they work well, there needs to be a step-change towards broad panel testing by next-generation sequencing. This combines testing for all potential genetic actionable alterations in one panel with data aggregation and analysis, and expert review to provide a curated, quality-controlled report to help physicians identify targeted or immunotherapy treatment options.

The implementation of next-generation sequencing, however, is dependent on the availability of resources, Krebs said, as it is not just a question of a sample being loaded onto a machine. He underlined that expert input is required to reliably interpret the results and determine whether they are significant. This has been a likely factor in delaying more widespread adoption in the clinical setting.

Another aspect affecting the take-up of molecular diagnostics in lung cancer is the question of tissue versus liquid biopsy. Tissue-based genomic profiling remains the standard of care, due to its higher sensitivity for certain types of alterations, but frequently there may not be enough material for molecular testing, the obtaining of biopsies is itself challenging and poses risks to the patient, and tissue biopsies do not capture the heterogeneity of the tumour.

Liquid biopsy has, on the other hand, evolved enormously in recent years and can help in profiling patients, as a reliable result can be obtained simply by drawing a blood sample. This can be analysed by extracting tumour-derived DNA, with results turned around usually within 10–14 days. Due to its simplicity, it could, be applied at various steps along the care pathway, from screening and initial diagnosis (although highly sensitive technologies would be required for this purpose) and prognostic assessment to therapy response monitoring, detection of resistance mechanisms and recurrence surveillance. It is also able to better capture tumour heterogeneity compared with single site biopsies. However, it will not provide answers for all patients, Krebs noted, and tissue biopsy testing consequently remains important. The two are complementary.

For some patients who do not have identifiable genetic alterations, immunotherapy has become a back-bone of therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. There is, however, a lack of good biomarkers for selecting patients who are most likely to benefit from this therapy. Assessing the tumour mutational burden may help in identifying patients who could benefit from immunotherapy as monotherapy. Together with genetic profiling in liquid biopsy, this can help inform clinical decision making in non-small cell lung cancer and guide patients to targeted versus immuno-and chemotherapy, as is being investigated in the ongoing B-FAST trial.[14]

Krebs said that the question nevertheless remains as to how to integrate these advanced diagnostic tools into routine clinical practice.

Quality of Testing is Key

In the following discussion, Joanna Chorostowska, Secretary General of the European Respiratory Society, said that, while there is a tight link between molecular diagnostics and diagnostics per se, the quality of the testing is key, as that determines the quality of treatment. Crucially, the higher the quality of the sample, the better the results.

She said that the EQRCC: Lung Cancer[1] is fundamental, as it highlights the complexity of the clinical process and the need to come together to provide high quality services all along the cancer pathway. Within that, the MDT should be much more than a meeting over a few hours but the basis for the effective organisation of healthcare.

Chorostowska also underlined that, while pathological examination enables the diagnosis of lung cancer type and, optimally, its subtype, molecular diagnostics enable the detection of predictive biomarkers that direct therapeutic decisions. They therefore offer very different types of information. Molecular testing consequently does not replace pathological assessment and will not for the foreseeable future.

Empowering Patients

Next, Anne-Marie Baird, from Lung Cancer Europe, underlined the inequalities in the availability of molecular diagnostic testing both between and within countries, and that huge advances in technology are not always translated to the clinic in an acceptable timeframe. In addition, a proper biomarker needs to be associated with every drug to maximise benefits and minimise toxicities.

Alongside that, it remains the case that simply many people do not know what type of lung cancer they have, whether or not their tumour has undergone genetic testing, let alone whether the result was positive or negative. Clinical communication should be very clear; if not, it means that people may look for information elsewhere and a general search for lung cancer would yield overwhelming results. People with lung cancer also need to be empowered to ask the most pertinent and important questions about testing, treatment and their overall care.

A Hopeful Future

Addressing Baird’s observations on the inequalities around the availability of molecular testing, Marc Beishon, co-author of the Essential Requirements for Quality Cancer Care: Lung Cancer, noted that the approach of the paper is to map the organisation and resources needed to deliver the current, and essential, standard of care, which many do not receive.

Simon Oberst, Co-Chair of the European Cancer Organisation’s Quality Cancer Care Network, remarked that it would be interesting to know the health economics of liquid biopsies and next-generation sequencing, while Jan van Meerbeeck, from the European Respiratory Society, questioned whether liquid biopsy should be available to all patients, without prescription.

Closing the session, Oxnard said that the discussion has left him hopeful as, despite the stigma surrounding lung cancer, there is optimism over innovative medicines becoming more available for patients, even those with the most advanced disease. Innovative testing will also allow for more precision care. Yet access to these innovations is key, and tests need to be leveraged to provide patients with more information.