Treating the Person Not the Number: Improving Care for Older Cancer Patients

The Treating Ageing Patients with Cancer session was chaired Matti Aapro, President of the European Cancer Organisation & EU Cancer Mission Assembly Member, and co-chaired by Hampton Shaddock, Head, Global Public Affairs, Oncology at Sanofi.

Counting the Cost of Cancer Care

Peter Lindgren, Managing Director of The Swedish Institute for Health Economics, opened the session by highlighting that cancer is an age-associated disease, and the ageing people population has led to a 50% increase in cancer incidence and a 20% increase in cancer mortality since the mid-1990s.1

This has had enormous consequences for healthcare systems, with a 86% per capita increase in direct cancer costs over the same period.2 This is in part due to demographic shifts but also to innovations in management and therapies that have improved survivorship.

While cost of newer oral cancer therapies has been partially offset by a move towards more outpatient care, the transition in some instances to a more chronic condition has led to consequences both for healthcare services and the wider care economy.

Older Patients Often Treated Blindly

The importance of this is underlined by the fact that one-third of cancer patients are older, said Professor Etienne Brain, Co-Chair Corporate Relations Committee for SIOG and Department of Clinical Research & Medical Oncology, Institut Curie. This means that all adults oncologists are geriatric oncologists, they just do not know it yet.

Older cancer patients nevertheless often find themselves in the position of either being victims of therapeutic nihilism, in which they do not receive any treatment, or blind therapeutic enthusiasm, in which they are given futile or non-beneficial treatments.

Kathy Oliver, Vice-Chair of the European Cancer Organisation’s Patient Advisory Committee, reminded the audience that the issues of cancer care in older patients were underlined by the COVID-19 pandemic.

There were instances of patients being excluded from decision making and denied the opportunity for consent, and she warned that older patients can end up being seen as a double burden.

Conflicting Priorities Between Young and Old

Professor Brain said part of the problem is a gap between the way society views older patients and their needs, a key aspect of which is frailty. There is typically a focus on the tumour extent and biology, as well as patient preferences and treatment acceptability, but less consideration of patients’ general health status and treatment toxicity.

Comparing the management of younger and older cancer patients highlights several apparently conflicting sets of priorities, he said, such as the quantity versus the quality of life, treatment response versus cognition and functional status, and the molecular status of the disease versus the global status of the patient.

He said that geriatric assessments can nevertheless result in modifications of the initial treatment plan in approximately two fifth of cases, and the use of less intensive treatments in around two thirds3. Moreover, they lead to greater emphasis on the functional and nutritional status of the patient.

Professor Brain said that, to allow closer cooperation between oncologists and geriatricians, clinicians and policymakers need to be disruptive in the organisation of care and inclusive in their language, as well as train younger generations in geriatric oncology.

Change at All Levels

This need for broad changes was endorsed by Dr Enrique Soto, from the Older Adults Task Force of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. He said the issue cannot be solved simply by changing how doctors treat patients but by tackling the ageism that exists at all levels of society.

It needs to be easier for cancer patients to achieve age-appropriate care, and the largely administrative barriers that physicians encounter in caring for older adults need to be lifted. He said that cancer healthcare professionals are already convinced of the need to perform geriatric-aware assessments but they do not have the tools available.

One initiative could be to develop a simple geriatric assessment replicable across care settings that allows for patients to be identified and treatments to be modified, all in a research-mindful manner.

Building Systems that Meet Patient Needs

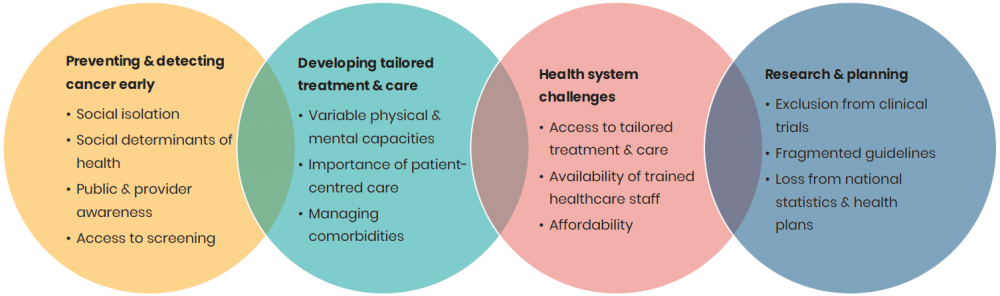

In the final presentation, Dr Cary Adams, Chief Executive Officer of the Union for International Cancer Control, said that the longevity revolution means that policies specific to older patients need to be developed that will improve health promotion and prevention, alongside building health systems responsive to their unique needs (Figure 1).

This will require research and planning, and coordinated policy responses on a national, regional and even global level, all backed by coordinated investment.

He emphasised that every country should have a robust, comprehensive, fully funded and implemented NCCP that reflects the challenges and needs of older patients. A good example is France, where older patients were specifically included in their cancer plan. Through coordinated investment, and the development of priority actions and networks, there are now 28 geriatric oncology units across the country.

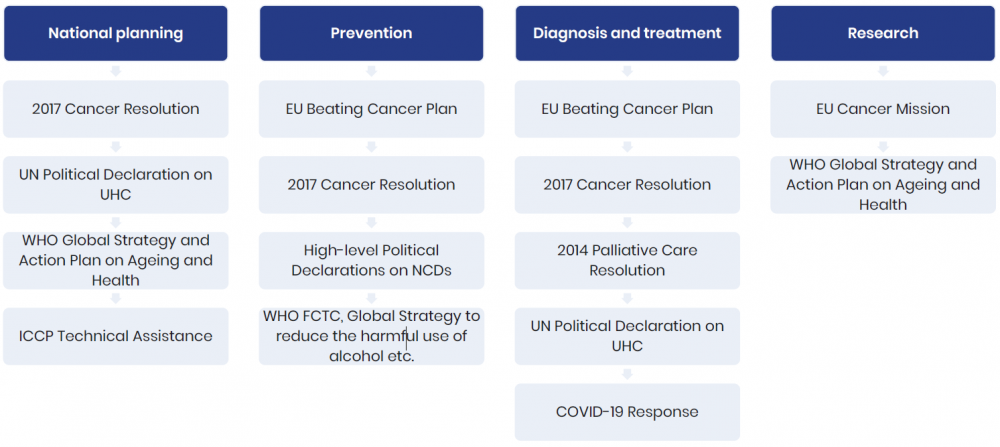

Dr Adams believes that money should be diverted to non-communicable diseases on a European Union level, and that the common needs of the ageing population across the region is an opportunity for joint advocacy across diseases. This means connecting different ranges of action at a national level across prevention, diagnosis and treatment, survivorship and research (Figure 2).

While this can be challenging, the aim must be to ensure that the older cancer patient is included in all initiatives, and at all levels.

Figure 1. Recognising unique needs

Older adults have a series of unique needs which interact and introduces additional complexity in managing cancer across every health system.

Figure 2. Connecting different levels of action

Meeting the Unique Challenges of Ageing Cancer Patients

The Treating Ageing Patients with Cancer session was co-chaired by Hampton Shaddock, Head, Global Public Affairs, Oncology at Sanofi.

“The convergence of ageing and cancer creates a tidal wave that will place significant burden not only on individuals, but on their families, communities, societies, economies and healthcare systems worldwide. Unfortunately, most societies around the world are not equipped to address the societal and economic implications associated with this rise.”

“This is exactly why Sanofi launched the When Cancer Grows Old initiative on World Cancer Day 2020 to help address the unique challenges faced by ageing cancer patients and their caregivers, including an often complex patient journey. We are hopeful that Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan can be implemented at national-level in a way that is inclusive and responsive of the unique needs of ageing patients with cancer, so that the WHO’s Decade for Health Ageing can be a reality for all.”

References

1. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer 2018 11; 103: 356–87.

2. Hofmarcher T, Lindgren P, Wilking N, et al. The cost of cancer in Europe 2018. Eur J Cancer 2020; 129: 41–9.

3. Hamaker M, Schiphorst A, ten Bokkel Huinink D, et al. The effect of a geriatric evaluation on treatment decisions for older cancer patients--a systematic review. Acta Oncol 2014; 53: 289–96.