2. Information

You have a right to:

Information about your disease and treatment from your medical team and other reliable sources, including patient and professional organisations.

Three key questions that every cancer patient may choose to ask:

- Will I be able to decide how much information I should receive about my diagnosis, treatment (including the benefits and risks) and the management of my disease?

- May I bring a relative or friend to my consultations?

- Will I receive written information about my cancer and will I be given contact details for relevant patient organisations?

Explanation

European cancer patients are entitled to reliable, good quality, comprehensive information from their hospital about their disease, its treatment and the consequences of that treatment. Patients should be informed that they can ask questions about the diagnosis, treatment and the consequences of the disease and/or its treatment, as well as receiving information on nutrition, physical activity, psychological aspects, etc. The hospital should also refer the patient to patient organisations which can provide invaluable information and support at many levels. In some countries, patient organisations and hospitals organise information sessions for newly diagnosed patients, so that all their questions can be answered and ideas exchanged .

Although patients are entitled to all relevant and comprehensive information if they so wish, how much information a patient wants about their cancer is up to that individual. Some patients prefer to be given a relatively small amount of basic information, leaving the complexities to their healthcare professionals. However, increasingly most patients want to have a clear picture of their illness, how it can be treated and to receive sufficient information to be able to make informed decisions about their care and be reassured that the treatment they will receive will be the best available for them.

Healthcare professionals will, in good modern clinical practice, explain to patients the nature of their illness, its extent and how that is measured, and the options for treatment and their likely outcomes. Explanations may come from the doctors or other members of the healthcare team. Cancer nurses will often have special communication skills and actively contribute to the consultation, either jointly with other healthcare professionals or individually and separately with the patients as required. The patient has the right to have someone of their choice with them during consultations and communications, often a close family member or friend. They have the right to ask for information to be repeated in a meeting or in subsequent meetings and presented to them in language that is accessible and clear. Consultations may be recorded if a patient so wishes and with the consent of others present at the time, and the recordings used by the patient as a record and reminder of what was said. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many consultations have been performed online, to help ensure the safety of the cancer patient. Online advice on how to prepare for such consultations is available. It is important to ensure that patients are comfortable with this approach and that these consultations mirror, in as much as is possible, the face-to-face consultation. Patients should have the right to choose which type of consultation best suits their needs and situation.

Information given at a consultation should be supported with good quality, relevant and clearly-written material provided by healthcare professionals, with appropriate explanations for the individual patient. Valuable written material is also available from patient advocacy organisations in many European countries. Guiding patients to reliable online material for subsequent reading is also important. Patients will often access information themselves online. Healthcare professionals should be prepared to answer questions about online findings and in particular relate this information to the patient’s individual cancer journey. Some websites will be highly evidence-based, while others will be more speculative. Engagement with healthcare professionals and patient advocacy organisations should help patients and their carers to successfully navigate online cancer advice.

Supporting Literature and Evidence

Good communication is central to the provision of excellence in patient-centred care (59), especially when it underpins decisions and choices about diagnosis and treatment. Patient-centred approaches that depend on good communication are now built into the philosophy, culture and operational frameworks of many healthcare services. Patients should have the opportunity to make informed decisions about their care and treatment, in partnership with their healthcare professionals. Similarly, the Institute of Medicine (IoM) states that healthcare professionals should provide ‘care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’ (111). Excellence in patient-centred care requires informed decision-making following good communication and provision of good-quality information.

Good communication is a feature of every aspect of cancer care (7, 59). Communication skills training is now an important part of undergraduate education in healthcare and of continuing professional education in all oncology disciplines. Advanced communication skills in cancer professionals bring benefits to cancer patients (112). Many areas require training, including breaking bad news (113) and explaining complex treatments and clinical trials. In all clinical settings, healthcare professionals are taught that good communication begins with a courteous introduction, ensuring that a patient knows who you are and what you are there to do. Training encourages health professionals to tell the truth and try to listen as much as you talk. Beyond these social norms, however, an organised approach to communication is helpful.

Patients preparing for a consultation

The Association of European Cancer Leagues Patient Support Working Group (114) has produced a structured guide on how a patient may prepare for a medical consultation.

Before the consultation: Ask a relative, friend, partner, carer or advocate to accompany you to your appointments, make a list of questions you would like an answer to, make a list of all medicines and pills you take, including vitamins and supplements, write down details of your symptoms, including when they started and what makes them better or worse, do not be afraid to ask your doctors to repeat and/or clarify anything they say, ask if you can record consultations on your smartphone.

Before you leave: Check you have asked all the questions on your list, know what the next steps are, ask who you can contact if you have any problems or further questions, ask for reliable sources of information about your disease and treatment options.

After the consultation: Keep all your notes safe - in case you ever need to refer to them, book dates for the next appointments in your diary, discuss the results of the consultation with your loved ones

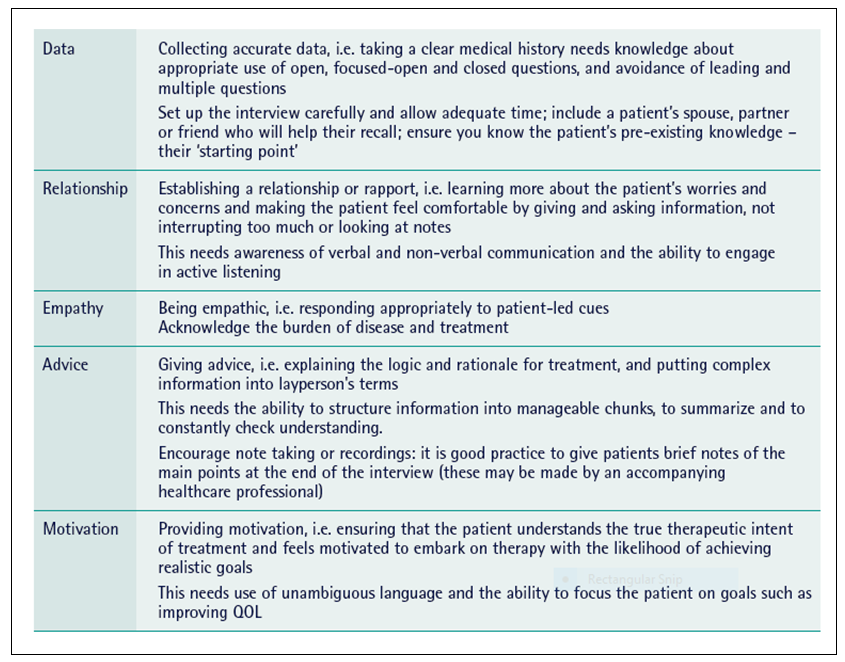

The DREAM protocol to aid professionals in communication

A well-structured example of a specific approach to aid cancer professionals to communicate confidently and well is the DREAM five-component protocol. (5, 59). Table 3 uses the DREAM outline to summarise the features of an approach to good communication with cancer patients. It is clear that patients usually want information about treatment options to be communicated carefully and honestly. There are increasing ethical, legal and social imperatives for patients to be more active and engaged in their care decisions and to be autonomous and collaborative rather than passive in decision making. As articulated by the European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety Tonio Borg at the launch of the European Cancer Patient Bill of Rights in the European Parliament on World Cancer Day 2014, patients should be “active participants rather than passive recipients” (2-3).

These imperatives are becoming arguably even more important now that so many complex treatment options exist for many cancer patients. Implicit in the term ‘informed consent’ is the idea that patients are told about the potential harms and benefits of different management plans, including any appropriate alternative (such as clinical trial enrolment) and have the opportunity to ask questions about the logic and rationale behind any suggestions before they give their consent. Unfortunately, studies in the past 20 years across tumour sites have shown that there is often a mismatch between patients’ understanding of information, their decision-making preferences and what actually occurs in clinical consultations.

Table 3. The DREAM interview: key components and skills needed by cancer professionals conducting consultations (59)